EU countries should adopt CC-0 licensing to maximise the benefits and usability of open data–including by OpenStreetMap.

EU Directive 2019/1024–better known as the Open Data Directive–will soon open up new datasets from governments across the European Union. Luxembourg, for example, has already adopted a formal recommendation strongly advocating application of the CC-0 licence for all open datasets, which has already been applied to geo-datasets since released.

This is great news for Europe and the world. It could also be great for OpenStreetMap and the vast audience that depends on it. But for that to happen, the officials who are now finalising their data release plans must avoid a subtle but critical mistake: they should release their data using the Creative Commons CC-0 license rather than the more popular CC-BY 4.0 license.

Explaining why this is so requires some background. It is common for geographic datasets to be released under licenses that specify how the data must be credited, how it may be transformed or redistributed, and who is allowed to use it. OpenStreetMap combines geodata from many sources to make a unified map of the world. Combining data isn’t always easy. Combining licenses can be even harder.

An example might help. Imagine a government agency releases geodata with a requirement that any map made from it be updated when the agency publishes new data. In isolation, this sounds reasonable. Agency workers diligently update the information they publish. It makes sense for them to ask those who use it to be similarly assiduous in not spreading outdated information. But what happens when the data is combined and redistributed with dozens of other datasets with similar requirements? Or hundreds? Or when it’s partially edited to reflect changes about the world?

Maybe you can imagine some solutions to this particular problem. Trust us when we say: it’s impossible to imagine a solution to every license problem. The potential for license conflicts means that OpenStreetMap must be very careful about the data we allow into our project. Licenses have to be checked for compatibility with the project’s own license to ensure that including a new data source will not interfere with the countless ways that OpenStreetMap data is being used around the world.

And those uses are immensely valuable. It is surely not a coincidence that the Annex I to the Open Data Directive lists “geospatial” first among the high-value dataset themes targeted by the initiative. Maps are useful to every person, business, and institution. And OpenStreetMap has become a key part of how map data reaches people around the world. Our project is used by many of the most popular mapping platforms, reaching an audience that numbers in the billions. Perhaps more importantly, OpenStreetMap is free for anyone to use. We think this makes our project an ideal partner for the Open Data Directive’s goal of unlocking “public sector data for re-use, as raw material for innovation across all economic sectors.”

But for that to happen, the data must be released with a license that OpenStreetMap can use. The Directive’s implementing regulation provides licensing guidance for the officials who have been given this responsibility:

It is the objective of Directive (EU) 2019/1024 to promote the use of standard public licences available online for re-using public sector information. The Commission’s Guidelines on recommended standard licences, datasets and charging for the re-use of documents identify Creative Commons (‘CC’) licences as an example of recommended standard public licences. CC licences are developed by a non-profit organisation and have become a leading licensing solution for public sector information, research results and cultural domain material across the world. It is therefore necessary to refer in this Implementing Regulation to the most recent version of the CC licence suite, namely CC 4.0. A licence equivalent to the CC licence suite may include additional arrangements, such as the obligation on the re-user to include updates provided by the data holder and to specify when the data were last updated, as long as they do not restrict the possibilities for re-using the data.

High-value datasets shall be made available for re-use under the conditions of the Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication (CC0) or, alternatively, the Creative Commons BY 4.0 licence, or any equivalent or less restrictive open licence, as set out in the Annex, allowing for unrestricted re-use. A requirement of attribution, giving the credit to the licensor, can additionally be required by the licensor.

cf Directive (EU) 2019/1024 Impact Assessment

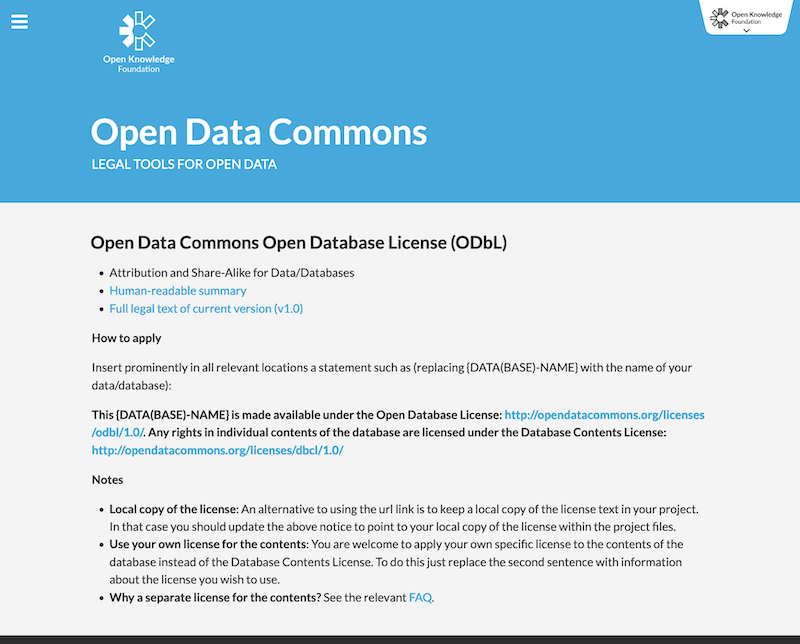

Unfortunately, OpenStreetMap cannot use data licensed under CC-BY 4.0 without additional caveats. The reasons are subtle but important; you can read about them here. The authors of the Directive guidance might not have realised this. We know that many officials are familiar with CC-BY. But as the above link explains, CC-BY carries more restrictions than just a requirement of attribution. Article 2’s intent is clear: it means to “ensure that public data of highest socio-economic potential are made available for re-use with minimal legal and technical restriction and free of charge.” The officials charged with executing that intent should choose CC-0 instead of CC-BY.

We realize that this might not always be possible. When that’s the case, officials should consider licensing their CC-BY 4.0 data with less restrictive terms, as allowed by Article 4. The License Working Group has supplied simple language that officials can include to make CC-BY 4.0 less restrictive and the data published under it unambiguously usable by OpenStreetMap:

Section 2(a)(5)(B) of the CC BY 4.0 license is void. Attribution to a central list of sources via URL is sufficient to provide attribution in a "reasonable manner" in accordance with Section 3(a)(1) of the CC BY 4.0 license.

OpenStreetMap is among the world’s most successful open data projects. If the right decisions are made as its implementation is finalised, the EU Open Data Directive could become one, too.