“Eddies,” said Ford, “in the space-time continuum.” “Ah,” nodded Arthur, “is he? Is he?”

“What?” said Ford. “Er, who,” said Arthur, “is Eddy, then, exactly, then?”

…

Why,” he said, “is there a sofa in that field?”

“I told you!” shouted Ford, leaping to his feet. “Eddies in the space-time continuum!”

“And this is his sofa, is it?” asked Arthur, struggling to his feet and, he hoped, though not very optimistically, to his senses.

Jump onto Eddy’s sofa for a moment and fast forward to a possible 2015.

After the

location wars of 2010, the problems of mutually incompatible geographic identifiers have been solved with the formation of the Global Places Register. Founded by a fledgling startup on the outskirts of Bangalore, the GPR offered an open and free way for individuals and corporations to add their town, their business, their POI. All places added became part of the Global Places Translator, allowing

Yahoo’s WOEIDs to be transformed into

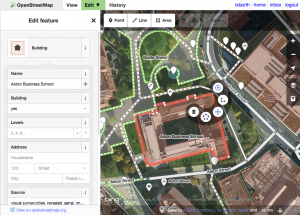

OpenStreetMap Ways, into long/lat centroids, into

GeoNames ids or even, for the nostalgic,

Eastings and Northings.

With this thorny problem solved, location issues became a thing of the past, no one used the phrase ubiquitous location any more and location really was a key context.

Until 2014 when, inspired by the move from CDDB to Gracenote, Global Places Pty Ltd promptly ringfenced the entire database under a commercial license and added a mandatory application id to all their APIs. An application id that cost a lot of money in licensing.

Of course, the fact that the GPR was now the sole global source of places doesn’t mean that it’s complete or authoritative. Being controlled by a single corporation, the GPR is an easy and obvious target for hacking and litigation. A dedicated team spends all their time removing places and POIs from the register that have offensive or religious connotations, either as a result of user generated contributions or malicious hacking.

Sadly, the cities of London in Ontario and Ohio are no longer found in the GPR; they’ve had to rename themselves after a successful trademark and copyright case brought by London in the United Kingdom, which is now the sole place in the world allowed to call itself by that name. This does make geodisambiguation a bit easier though.

Likewise, you won’t find any newsagent or newsstand POIs in the GPR; they were all removed following a successful DMCA takedown by the League of Concerned Conservative Fundamentalist Parents, who didn’t want their precious offspring to be able to locate purveyors of potentially offensive adult material on their GPR powered LBS apps on their Android mobile internet tablets.

The same goes for any business with the word jolly in it; they were all removed and forced to rebrand following the success of Jolly Jet trademarking the word jolly and then pursuing an aggressive litigation program against any business unfortunate enough to have that word as part of their name.

This is all just a geographical bad dream. It’s not real. Wake up. Back to 2010 now, safe and secure in the knowledge that this could never happen …

Yet there is a growing clarion call for an open global database of places, POIs and business listings that will allow all of the disparate geographic identifier systems to be rationalised and used interchangeably. It’s the problem of what I’ve started calling GeoBabel but an actual global database of places isn’t the solution to this problem.