During the course of history, we have used several types of tests to tell if something is what it seems to be, or to check if it is up to expectations.

Now we use industrial stress tests, quality assurance checklists and software metrics. We put dummies inside of cars and crash them into concrete walls at full speed, to check if the dummy gets out in one piece or not; then we decide whether the car is safe enough. Centuries ago, the church used the trial by water ordeal: tie a rock to a woman’s leg and throw her into a lake; if she drowns, she’s not a witch; if she comes back to the surface, she is a witch and has to die by burning.

Free software also has tests, which are scientifically more accurate than the trial by water, as one has to tell apart free-as-in-free-beer licenses from free-as-in-free-speech ones. During the development of free software licenses (such as the GPL) in the 90s, there are some tests which are well-known amongst free software advocates: the “desert island test”, the “dissident test” and the “tentacles of evil test”. These test were an integral part of the Debian Free Software Guidelines (or DFSG for short). The DFSG are just a definition, and are not easy to explain to a layman: it’s better to check against some use cases.

For example, the “desert island test” assumes a castaway in a desert island with a solar-powered laptop, and some software in it. For this software to be free, the castaway has to not be legally forced to distribute any changes made to that software, as he just can’t. Technically, this test checks that the license asks for source code redistribution only when the binaries are distributed. This tests makes it easier to understand whether a license complies with the DFSG, rather than checking against the DFSG themselves.

And what about geographical information? Is there any test that lets us know whether or not the information from National Mapping Agencies (NMAs) or Spatial Data Infrastructures (SDIs) is really available under conditions that allow the citizenship to make the most out of them?

In order to know if a given set of geographical information can be considered free (as in free speech) or open or “libre”, it can be checked against the Open Knowledge Definition (OKF), just as free software can be checked against the DFSG. However, the OKF can be a bit dense for laymen.

There is no easy test to know if a set of geodata is free/open/libre or not.

Until now.

I hereby propose the Cake Test.

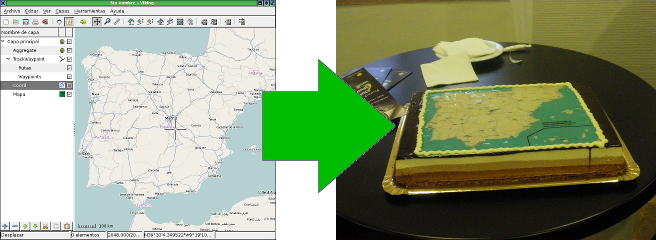

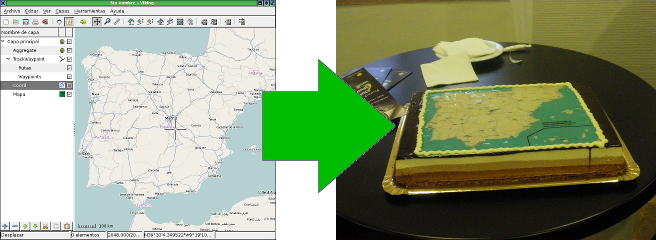

What is the Cake Test? Easy: A set of geodata, or a map, is libre only if somebody can give you a cake with that map on top, as a present.

Cakes are empirical proof that most the data in most SDIs cannot be used freely, because of the licensing terms of the SDIs. And they are an empirical proof that attendants to the latest spanish SDI conference could taste themselves.

Even if maps, or geodata, are published in a web site for free (at no cost), it doesn’t mean that a cake can be made with them. Some examples of technical or legal obstacles for the “cakefication” of geodata are:

- Not being able to download the geodata to a computer.

- Not being able to copy the geodata to a different medium, or not being able to redistribute it. In order to make the cake, a bakery needs a CD with the images, or an e-mail with them.

- Not being able to use the maps for profit (AKA “commercial use”), even if the person giving the cake away is not making any profit (AKA “indirect commercial use”). The one giving the cake does not make money, but the bakery does.

- The obligation to sign a license (or such) for commercial use. Do you really expect people to go to a bakery and say “hey, I’d like a cake, but you need to sign this commercial-use-of-geodata-license thing first”?

- The obligation to notify any usage of the geodata prior to using it. If we have to tell we’re making a cake, it wouldn’t be a surprise, would it?

A set of geodata must comply with lots of conditions in order to bake a cake with it, and may seem complex when applied to a geodata license (and the Cake Test is just a neccesary condition, not a sufficient one), but the goal of the Cake Test is very simple:

If a layman can’t decide whether he can or can’t decive if he is able to give away a cake as a present, or plainly isn’t able to, then the geodata cannot be used freely, is not free, and is not libre.

On the other hand, if some day someone gives a NMA or SDI a cake as a present, then that NMA or SDI is on the right track for information reuse. And the day that happens, they’ll probably throw a party, as they’d already have the cake.

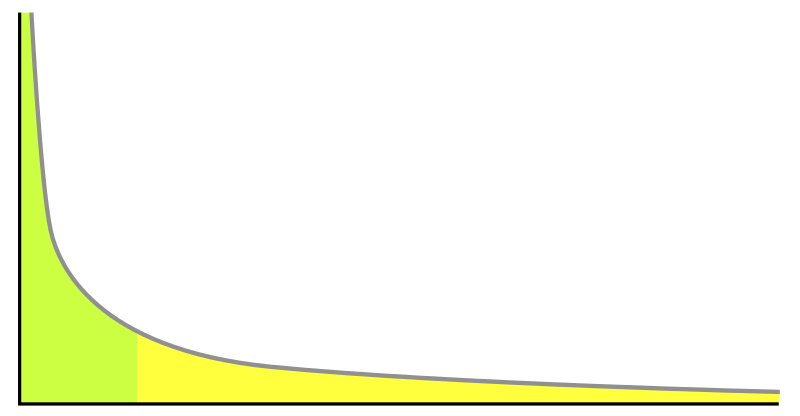

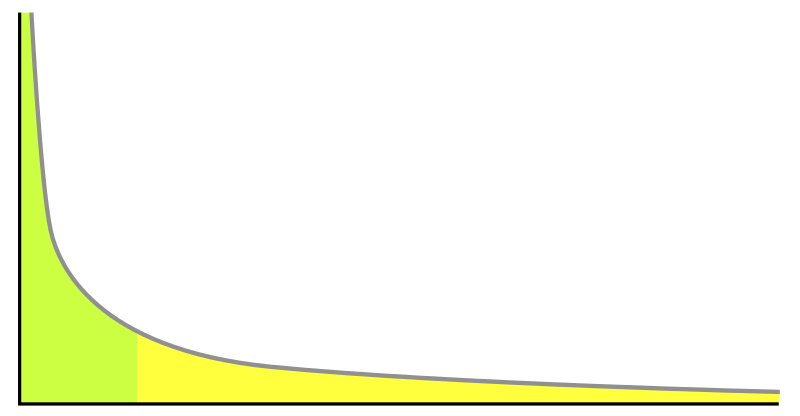

The Cake Test also illustrates the concept of long tail.

Usually SDIs and geoportals are built in order to the big geodata consumers to generate more profit, or lower their costs. This is the green section of the graph: quite few data consumers, but consuming a lot of data involving a lot of money. They are government agencies, and big corporations and projects. On the other end of the graph, in the yellow section, would be them cakes.

Obviously, cartography applied on top of pastry products is just a marginal contribution to a country’s Gross Income. But it’s not a null contribution and, most probably, no one thought about it before.

The long tail is full of cakes and other marvellous things that haven’t been invented yet. How many new uses for geodata are there to be discovered? How long is cartography’s long tail? The only certain thing is that, in order to know that, free use of geodata has to be encouraged.

(This is a translation of an article originally in Spanish, available here)